The Understood-Understanding Gap: Why LLMs Hit a Wall

Large Language Models have become ubiquitous in knowledge work, yet a curious pattern has emerged. Talk to consultants at McKinsey, BCG, Bain, and you'll hear the same refrain: "I don't really know how I can leverage AI to boost my productivity beyond research and brainstorming." The same applies to programmers, LLMs excel at boilerplate but falter when problems require sustained, coherent reasoning.

This isn't a bug to be fixed with better prompting or longer context windows. It's a fundamental limitation of what these systems actually are.

What LLMs Actually Are: Statistical Contextual Models

To understand the limitation, we need precision about what these systems do. LLMs should more accurately be called Statistical Contextual Models. They operate on two principles:

- Statistical patterns learned from training data, the regularities, correlations, and structures found in text

- Contextual attention via the transformer architecture, the ability to weigh relevance of different parts of input when generating output

The transformer architecture was revolutionary. It gave AI the ability to contextualize inference—to consider how different pieces of information relate to each other. This created the impression of understanding. But contextualization and understanding are not the same thing.

Understood vs. Understanding

Here's the critical distinction:

Understood is the residue, patterns, correlations, and structures frozen in training data. It's what has been comprehended by others and encoded into text that the model has seen.

Understanding is the active process of grasping relationships, causality, and structure in real-time. It's the construction of working models of novel problems.

LLMs operate entirely in the domain of understood. No matter how sophisticated the contextual attention mechanism, they remain fundamentally retrieval and recombination systems. They predict what tokens would appear in text written by someone who understood the problem, but this is not the same as understanding the problem itself.

Why Consultants Hit the Wall

Consider a consultant working on organizational transformation. They describe the client's situation to an LLM: declining revenue, siloed departments, recent leadership turnover, resistance to change initiatives.

The LLM can:

- Match these patterns to similar situations in its training data

- Retrieve relevant frameworks (change management theory, organizational behavior concepts)

- Generate analysis that sounds insightful and sophisticated

- Recombine ideas in contextually appropriate ways

What it cannot do:

- Build a working ‘understanding’ model of this specific organization's dynamics

- Understand the unique interplay of personalities, incentives, and power structures

- Maintain coherent reasoning as the problem evolves across multiple conversations

- Distinguish between correlation and causation in this novel context

This is why consultants find LLMs useful for brainstorming but frustrating when formalizing problems. Brainstorming operates in the space of understood—generating ideas by recombining existing patterns. But formalizing a problem requires understanding, constructing a coherent model of what's actually happening and why.

The consultant hits this wall repeatedly: context gets bloated, copy-paste becomes tedious, and starting a new chat means losing everything because there was never a genuine understanding to lose, only a statistical contextualization of understood patterns.

Why Programmers Face the Same Limit

Programmers report similar experiences. LLMs are excellent at boilerplate code, standard patterns, common implementations, well-trodden solutions. But they struggle with:

- Maintaining architectural coherence across a large codebase

- Understanding the deep implications of design decisions

- Debugging novel interactions between components

- Reasoning about edge cases in genuinely new contexts

This isn't because the LLM "forgot" something or needs more context. It's because boilerplate operates in the space of understood (standard patterns to retrieve and adapt), while architectural reasoning requires understanding (building and maintaining a coherent model of the system).

When a programmer asks an LLM to debug a complex interaction, the model generates text that sounds like debugging reasoning. It pattern-matches to similar debugging scenarios in its training. But it's not actually modeling the causal chain of how data flows through the system, how state changes propagate, or why certain race conditions emerge.

The Palliative of More Context

The natural response to these limitations is: "We just need more context! Better memory! Longer context windows!"

But this is palliative, not curative. Even with infinite perfect context, a Statistical Contextual Model would still be doing the same thing: sophisticated pattern matching over understood material. It would not suddenly develop the ability to construct working models of novel problems.

More context helps maintain textual coherence, making sure the model doesn't contradict itself, keeping track of what's been said. But textual coherence is not conceptual understanding. The model isn't maintaining a coherent model of the problem; it's maintaining coherent text about the problem.

The In-Principle Limitation

This is not an engineering challenge to be solved with better architecture, more parameters, or clever prompting techniques. It's an in-principle limitation of the approach.

Statistical Contextual Models operate by:

- Freezing understood into weights during training

- Using contextual attention to retrieve and recombine relevant patterns

- Predicting tokens that would appear in text written by someone who understood

At no point in this process is there construction of understanding, the active modeling of causal structure, the building of working representations of novel problems, the genuine grasping of relationships that weren't already frozen in training.

This is why these systems can sound locally coherent but lose the thread globally. This is why they excel at tasks that operate in the space of understood but falter when genuine understanding is required. This is why no amount of prompt engineering can bridge the gap between brainstorming and formalization.

What This Means Going Forward

Statistical Contextual Models are remarkably useful tools for working with understood: research, brainstorming, boilerplate, retrieval, recombination. These are valuable capabilities.

But they are not, and cannot be, systems that understand. The consultant who wants AI to move beyond brainstorming is asking for a different kind of system entirely, one that constructs working models of problems, not one that retrieves patterns about problems.

The understood-understanding gap is not a bug in current LLMs. It's a description of what they fundamentally are.

Until we build systems that can construct understanding rather than retrieve understood, knowledge workers will continue hitting the same wall, finding these tools useful for certain tasks while frustrated by their inability to engage with problems at the level of genuine comprehension.

The question isn't how to prompt better or add more context. The question is whether we can build systems that understand, not just systems that have understood.

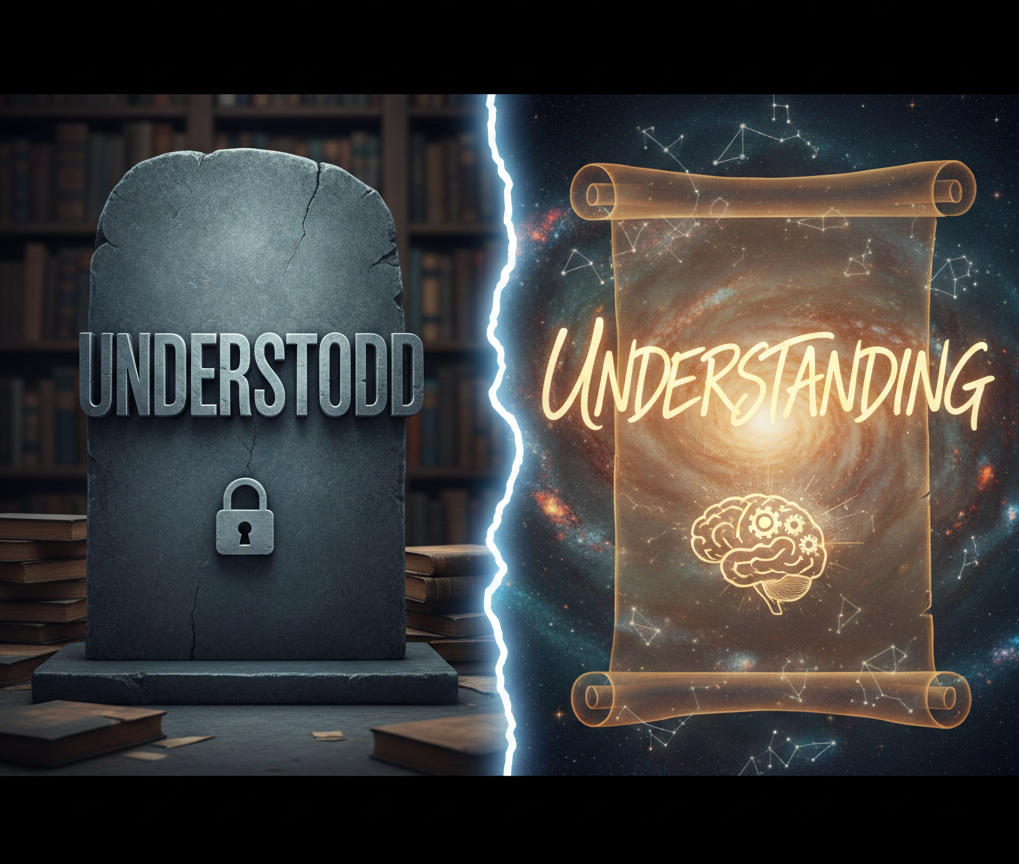

A Telling Example

As a concrete illustration of this limitation is the image above: when asked to produce an image depicting "understood vs understanding," a generative model can create a visually compelling representation. But there is no way to "explain" to the model to change "undertodd" (a typo it generated) into "understood."

Why? Because statistically, the verb "understood" does not appear often in that visual context. The model has no understanding of what it's depicting—only statistical patterns about what words and images co-occur. No amount of explanation bridges this gap, because explanation appeals to understanding, and the model operates solely in the domain of understood patterns.

This isn't a failure of the model—it's what the model is. And it reveals the fundamental nature of the limitation we're describing.